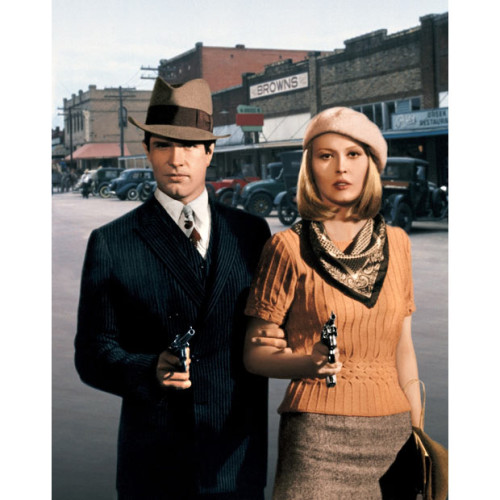

Bonnie and Clyde was an unforgettable movie in 1967, setting new cool fashion styles for the 1960s generation. For many young people the characters of Bonnie and Clyde, albeit the ruthless killers that they were, represented protesters of the government and the powerful. symbols of their own times in the 1960s. To older citizens the protagonists were murderers and losers, and the film was an orgy of violence. Among the latter was Jack Warner, head of the studio that made the movie. After screening the completed film he asked how long the movie was. When told, his reply was, “Well, that’s the longest {expletive} two hours and 15 minutes I’ve ever spent.” Warner subsequently refused to market the film, relegating its release to drive-ins and second-tier theaters. This from the studio that had made its mark in the 1930s with gangster films. But Bonnie and Clyde under Arthur Penn’s direction took movie violence to a new level. In the era of the Viet Nam war, the depiction of shootings by victims crumpling to the floor with no evidence of blood, was no longer going to cut it. In Bonnie and Clyde, explosive squibs of red color were amply used: men were shot in the face at point blank; and (spoiler) the multiple-shooter ambush of Bonnie and Clyde was filmed in slow-motion. The latter was inspired by Akira Kurasawa’s Seven Samurai. At one time, Francois Truffaut had been considered to direct the film. He was too busy but one of his ideas remained: some jump-cut editing popular with the French New Wave. No, this was not Jack Warner’s gangster film. But then shortly after, Jack Warner sold Warner Brothers to Seven Arts Productions. Warren Beatty was the producer, director and lead actor in Bonnie and Clyde, and he managed to convince the new owners to re-release the movie with wider distribution and marketing, with his agreement to a reduced profit participation.

The cast, a mix of new talent, character actors, and a veteran Broadway actress, was anchored by Warren Beatty. This was Faye Dunaway’s second movie and she almost stole the show, except for the goofy Michael J Pollard character of C.W. Moss, who made a big splash. It was also Gene Wilder’s first movie. It was nominated for eight Oscars: Best Picture; Actor; Actress; two Supporting Actors for Gene Hackman and Michael J. Pollard; Director; Costume Design; and Screenplay. It won Oscars for Best Supporting Actress for Estelle Parsons and Best Cinematography for Burnett Guffey. It was also the second-highest grossing film of the year for Warner Bros-Seven Arts.

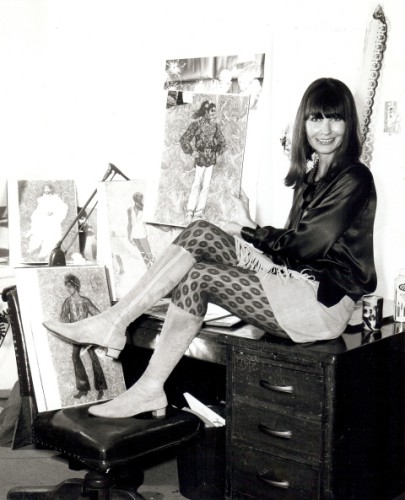

The positive side of the film’s influence was on fashion. With its mostly youthful audience, the beautiful Faye Dunaway struck a chic but devil-may-care attitude that fit the times just right. The costume designer was Theadora Van Runkle, a chic woman who could model the very clothes that Faye Dunaway wore. Like Miss Dunaway, Theadora Van Runkle was new to the movie business. She had been a fashion illustrator for the I.Magnin stores in Los Angeles. This was when art illustrations of new fashions were advertised in the newspapers. She had also done some costume illustrations for the Designer Renie for the movie Sand Pebbles starring Steve McQueen. She had gotten the Bonnie and Clyde job as a referral from designer Dorothy Jeakins. The job for any costume designer is to help develop character and advance the plot. In doing so Theadora looked over old photos of Bonnie and Clyde, and read the script, and in talking to director Arthur Penn and producer Warren Beatty, she developed ideas on how to dress the actors for their roles. She was self taught as a designer, and looked over old photos of gangsters and period clothes. Theadora once related that she was shopping for fabrics for Faye’s role as Bonnie and ran into Edith Head. She explained to the doyenne of costume design that the story took place in the 1930s. “Just dress her in chiffon,” was Edith’s advice. Although Theadora did not dress Faye Dunaway in chiffon, she impressed Warren Beatty and Arthur Penn with her costume sketches.

Costume sketch above for Faye Dunaway as Bonnie, signed at bottom, Theadora. The photo of Faye is shown below in the Norfolk jacket that was designed in the sketch.

Warren and Arthur wanted to put Faye in dresses, just like she appeared in the original photos, but with more style. Faye said that , “The look for Bonnie was smack out of the thirties, but glamorized and very beautiful….they were all cut on the bias and they swung.” The look of the smart skirts, paired with a form fitting sweater, Faye’s braless dressing, and a saucy beret cut an unforgettable image. This especially in Bonnie and Clyde’s line of work. As Bonnie stated, emphasizing each word, “We rob banks.” But it was Faye’s berets that launched a fashion trend. Theadora liked the look, taking off from a photo of Bonnie Parker wearing a beret-looking hat, and designed several of Faye’s outfits topped with a beret. When Faye Dunaway was in France after Bonnie and Clyde had premiered there, a box full of berets were delivered to her room at the ultra luxe George V hotel. They came from the village in the French Pyrenees where the traditional French berets were made. After the film came out demand in the U.S had caused production to jump from 5000 to 12,000 berets a week. American manufacturers were fabricating thousands of them as well. Skirts lengthened also as the long skirts in the film led to the trend toward maxi-skirts.

Theadora’s description in her sketch above reads: “Yoke & revers of black worsted navy & black striped worsted fagotted blouse of ivory silk”

The costume is shown in the photo below.

Warren Beatty’s costumes were common for men of the period. Most men in cities and towns, other than blue-collar workers, wore shirts and ties, often with vests. The cap was more working class than a fedora. The costume sketch below shows alternate shirt colors, although Warren wore mostly white shirts under his vest.

Theadora’s pencil notations on the sketch top right state, “All dressed up to rob a bank.”

Both the outfits of Bonnie and Clyde, Bonnie in her beret, sweater and and skirt, and Clyde in his vest, are the defining look of the “bank-robbing” “gangster” couple for costume parties and Halloween sorties.

Faye Dunaway looked fetching in black, as seen below. At this point in the movie they are on the road dodging the “manhunt” that has intensified. They are living out of their car and it’s hard to be glamorous. Yet the real Bonnie continued to write poetry and ballads until the end.

Theadora Van Runkle was nominated for three Best Costume Oscars: Bonnie and Clyde; Peggy Sue Got Married; and The Godfather Part II. She never won. She also designed Bullitt, Mame, Myra Breckinridge, The Thomas Crowne Affair, New York, New York, and The Jerk, among others. She died November 4, 2011.

Views: 14214