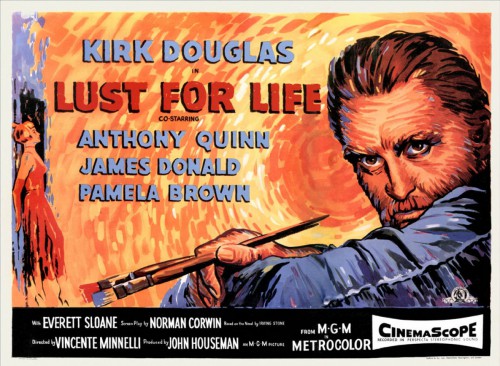

In the days when movie biopics were romanticized versions of their subjects, usually straying far from the truth, out came Lust for Life, the 1956 film depicting the tortured life of Vincent Van Gogh, blazingly acted on screen by Kirk Douglas. This was a raw and honest portrait of the artist as non-conformist, alienating almost everyone he knew, a searcher for meaning in his life and for the calling that could bring out the only talent he believed he had, though few saw it in him. This might be considered a typical view of of an artist or musician today, but it was ground-breaking in 1956.

Kirk Douglas and his Bryna production company was eager to do this film, and his resemblance to the artist, magnified with a beard and dyed red hair, was uncanny. John Houseman had produced Moulin Rouge to great success, based on the life of Toulouse-Lautrec, which was released in 1951. Vincente Minnelli was the best director, really the perfect director, for Lust for Life. He had been a costume designer and set designer in Chicago and on Broadway, and considered leaving to study art in Paris before he was hired by MGM. He knew how to show the dynamic of both the inner conflict of the artist/individualist and the problems caused by trying to fit into a society. He knew the soul of the artist, and how to involve art itself into the fabric of film and film’s methods of storytelling.

The movie begins when Van Gogh is 25, aspiring to be a minister as is his father. The church elders reject his application, since he can’t even deliver a sermon without reading it aloud. One of the elders takes pity on him, seeing his earnestness, and tells him to go to the Belgian Borinage coal mines and do services there (apparently no else wants to). Once there he realizes that the downtrodden people need little preaching, and more real help, which the church doesn’t provide. He gives away his clothes and the allowance he gets from the church. Upbraided by the elders for looking and living like one of the miners, he calls them all hypocrites and leaves his church calling.

Once back home with his family, he argues regularly with his father. His brother Theo understands him the most, but tells him he should overcome his idleness. Kirk Douglas passionately responds, there are two kinds of idleness, and he only wishes he was the first, but as he says, “I’m in a cage of shame and self-doubt.”

He finds expression through drawing, which he shows his sister in the photo below. The art he favors is the depiction of common people in their daily life and in drawing the countryside. But his odd demeanor and unkempt looks prove an embarrassment to his family. He goes to the Hague where his uncle is an art dealer that provides him with paints. He paints in monotones – such pieces as The Weaver or The Potato Eaters. He suffers from unrequited love with his first cousin, then takes up with a prostitute for a while. Theo is now also an art dealer in Paris, so Vincent joins him there and goes to the Impressionists art show and he meets Impressionist and other painters like Pissarro (trust your first impression he tells Van Gogh), Seurat (it’s all about the science of color he says), and Gauguin.

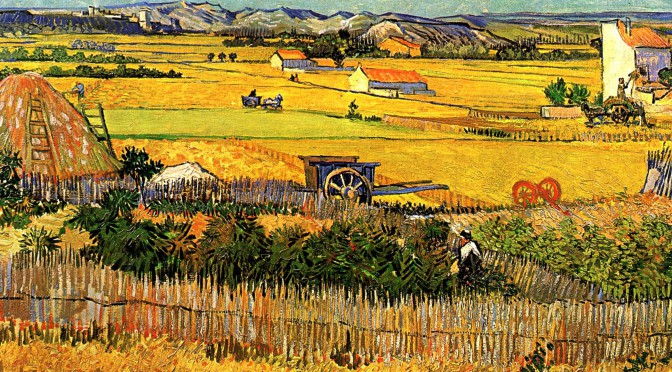

And then Van Gogh heads to the South of France – to Arles, “everything there is gold, bronze, copper and yellow,” he says in his letter to Theo. He first rents a cheap room but then rents a big “Yellow House” that he wants to make the “Studio of the South,” or a commune for the artists he met in Paris – to live and paint and exchange ideas. But Van Gogh is too much of the strident personality, without social skills, for them to come. In the meantime he paints every day, often speaking to no one. Theo is providing the rent money, and he urges Gauguin to join Vincent so as to encourage him. Gauguin has the forceful personality and thinks he can make it work. A sojourn in the South of France is better than the hard life of a merchant mariner, which Gauguin had been.

So Van Gogh and Gauguin live together in the Yellow House, although it does not take long before their personalities clash, and when the weather turns bad or the Mistral winds blow the canvases of their easels, they are confined to painting indoors, which Van Gogh loaths. Gauguin can paint from memory. Van Gogh paints from observation and the feeling associated with it.

At the cafe in Arles, which they frequent and drink absenthe with regularity, Van Gogh painted the scene , “The Night Cafe.” Drinking the alcoholic absenthe was rumored to be addictive, and along with Van Gogh’s other mental issues, possibly bipolar disorder or Asperger Syndrome, fueled his strong reactions.

Van Gogh’s and Gaugin’s arguments led Gauguin to saying he was leaving Arles, which in turn caused Van Gogh to threaten him with a razor blade. This led to the off-screen scene where Van Gogh actually cuts off part of his own ear – perhaps in an effort to cut his own throat, or as self mutillation, no one knows. The preceding scenes are dramatically acted by Kirk Douglas, his physicality shows his distress, alternating between threatening and abject, in shame and in terror.

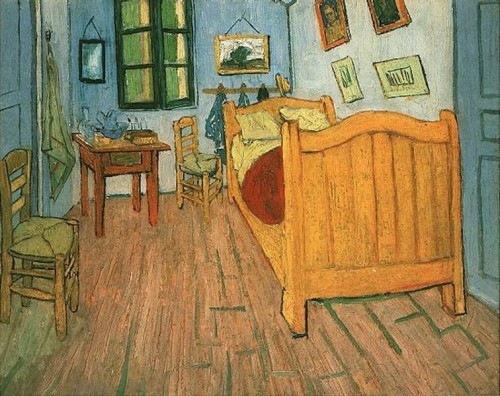

The photo below shows Kirk Douglas in the set rendition of the famous Van Gogh bedroom in the Yellow House in Arles, at Place Lamartine.

And as painted by the artist, the room was actually a trapezoid shape.

The ear episode ends up with more psychological trauma for Van Gogh – Gauguin leaves and Theo has his brother committed to an asylum, where Van Gogh sits days on end, saying or doing little. Eventually he returns to painting from his window, and then from the outdoors. A poignant scene has Kirk Douglas painting outside as a few of the inmates watch intently – a subliminal note by Minnelli on the power of art. But soon more psychological attacks follow, and Theo has him brought closer to Paris, to Auvers-sur-Oise, where he can be treated by Dr, Gachet. It is there that Van Gogh paints what is probably his last canvas. Wheatfield with Crows. It is indeed a foreboding work, dark skies, a road leading to nowhere, and the many crows, depicted in the movie as unintended subjects for the canvas, irritating Van Gogh to the point where he jabs black paint on his canvas in their shape, shortly before he shoots himself.

The screenplay for Lust for Life was written by Norman Corwin, using an episodic approach to Van Gogh’s life. As pointed out by Professor Drew Casper of the USC School of Cinematic Arts in the film’s DVD commentary, it has a five-part narrative which breaks down Van Gogh’s life into five parts, each structured around the letters he writes to Theo, which are narrated. The objective world as seen by Van Gogh is depicted in each of the five parts by at least one of his major paintings, separately seen. Each segment also had a color theme: black and gray in the Borinage; dark green in Holland; reds and blues in Paris; yellows and greens in the South of France; and multi-colored in Auvers.

The film was also richly complemented by the excellent costume designs of Walter Plunkett. Plunkett was one of the few designers that was equally adept at designing for both men and women. He conveyed the careless but individualistic dress of Van Gogh as well as the equally individualistic but almost dandy-working man dress of Gauguin – with his flashy and decorated vests and jackets – a purposeful magnet for the ladies. Walter Plunket also conveyed the full panoply of late 19th century France – the farmers and peasants, the red and blue soldier uniforms of the Zouaves, the decorated uniform of the facteur Roulin, the uniforms of the band, the traditional folk costumes of the women of Arles. All of this was of course accomplished through careful on-location research. The filming itself was mostly on-location in Holland, Belgium, Auvers, Arles, and the South of France. The cinematography of Freddie Young adds depth and beauty to the film.

The musical score composed by Miklos Rozsa evokes the settings and the emotions of the painter in a masterly way. Themes and moods are heightened by Rozsa’s compositions, conveying inner feelings of romance, pain, inertia, seizures, and even brief periods of contentment at painting in the plein-air.

Kirk Douglas said in his autobiography, The Ragman’s Son, that in performing the role of Van Gogh in Lust for Life, “It was the most painful movie I ever made.” And it took him a while to get over the role and the psychological effect it had on him. Douglas was nominated for Best-Actor for his role as Van Gogh, his third nomiation. Anthony Quinn was nominated for Best Supporting Actor. Everyone kept telling Douglas that he was a sure thing to get the Oscar. It was his third nomination after all, and there was little competition. He was in Munich Germany when the Academy Awards were held, making Paths of Glory. He said he had even practised looking surprised for all the photographers waiting in the lobby at his hotel. He was indeed surprised when he learned that Yule Brynner won for his role in The King and I. Anthony Quinn, however, won for Best Supporting Actor, the only award winner in the film.

Perhaps voters thought he over-acted. It is certainly a style of acting not much seen today. Lust for Life leaves an indelible image of the actor and of Van Gogh, a raw, powerful image as powerful as the canvases Van Gogh painted himself.

Views: 1167