This blog post looks back at the history of Paramount Pictures’ Wardrobe Department, its Golden Age costume designers, and its current Archives. An interview with Randall Thropp, the Manager of the Costumes and Prop Archives at Paramount is also included.

Movie history permeates the air at the Paramount Pictures Studio Archives. It might be difficult to realize these days, but Paramount was not born in Hollywood, California, but rather in New York, where in 1912 Adolph Zukor released the first full-length drama shown in the U.S; the French-made Queen Elizabeth, starring Sarah Bernhardt. At the time Adolph Zukor’s company was called Famous Players Film Company, which merged with the Jesse Lasky Company in 1916, and thus became Famous Players – Lasky. It soon took on the name of Paramount Pictures when it merged with Paramount Pictures film distributors. Lasky was making movies in Hollywood, having produced the first feature-length Hollywood movie in 1914, Cecil B. De Mille’s The Squaw Man. The latter was the first movie made in Hollywood, shot in and around a barn on Vine St. (now moved to Highland Avenue as the Hollywood Heritage Museum). Famous Players made its movies in Fort Lee, New Jersey, a thriving hub of studios in the early silent era, and in Astoria, New York. The new combined company took the name and logo of Paramount Pictures. Zukor followed Queen Elizabeth by hiring John Barrymore and Mary Pickford.

In 1926, Jesse Lasky built the Hollywood Paramount Pictures lot in the location where it still stands today, on Marathon Street at Bronson, adjacent to Melrose Boulevard. It comprised about 26 acres, with the usual admin building, several sound stages, outdoor standing sets, prop and costume departments, film-developing labs, and the rest.

The first credited costume designer for Paramount was Clare West. Ms. West had begun working for C.B De Mille. De Mille believed in the importance of costume in attracting the attention of viewers and helping “sell” his films. De Mille’s motto was “…don’t design anything anybody could possibly find in a store,” which he emphasized to his costume designers. Very soon his movies were known for the lavishness and excess of its costumes. As film production increased in the late teens and early 1920s, Clare West became the Wardrobe supervisor. She was there when Mitchell Leisen, an architect/set designer, came on and also became a costume designer. Another addition to De Mille’s costume designers was the flamboyant dancer Natasha Rambova, soon to become Rudolph Valentino’s wife. The multi-talented Rambova was also a set designer. She joined De Mille in company with Theodore Kosloff, the former Ballets Russe dancer, both as costume designers. They came to work on The Woman God Forgot in 1917. When De Mille found out it was Rambova that actually designed all the costumes, he kept her as a costume designer. She next designed the costumes for Why Change Your Wife in 1920 with Clare West, Forbidden Fruit 1921, with West and Leisen, and Monsieur Beaucaire 1924, starring her husband Valentino, where she also served as art director.

The wild 1919-1923 era of Hollywood costume design flowered when stars Leatrice Joy, Gloria Swanson and Pola Negri joined Paramount. The most lavish of costumes were invariably used in the De Mille spectaculars. Mitchell Leisen designed the Babylonian costumes for Gloria Swanson in Male and Female. Clare West and Howard Greer designed De Mille’s The Ten Commandments (1923). Greer had been a Chicago and New York designer of Broadway shows and had designed for the famous Lady Duff Gordon, aka, Lucile couture. Leisen started working as an assistant director for De Mille, so Greer took over as head designer when Clare West left in 1923. Although Greer could illustrate his own costume designs, he advertised for a sketch artist/assistant in 1923 because he was too busy. A young woman came in with “a carpetbag full of sketches.” Greer was very impressed by their diversity: architectural drawings, interior decoration, fashion design. etc. He hired her on the spot. When a very nervous Edith Head came in the next day she confessed and told him that she had borrowed the works from several of her fellow art students. Greer kept her anyway, no doubt remembering his own nervous first sketches for Lady Duff Gordon. Greer taught her how to illustrate fashion sketches – a necessity in showing the stars, directors, and producers, what the wardrobe would look like. And importantly, what the costume makers were going to be fabricating.

Not long after Edith Head joined Paramount, Travis Banton was hired to design the wardrobe for Leatrice Joy in The Dressmaker from Paris in 1925. The film’s tag line was having, for the first time anywhere, “the 1926 Paris fashions.” Such was the importance movie marketing now placed on film fashion, and the influence of the studio costume designer. Interestingly, Dressmaker was based on a scenario by Howard Hawks. It’s a curiosity that the director of such “manly” films as Scarface (the original version), The Big Sleep, and Rio Bravo wrote this script as well as Fig Leaves, (1926) which featured a fashion show designed by Adrian. One might expect that Howard Greer would become jealous of a new designer – also coming from New York and with experience with Madame Frances couture, where he had designed Mary Pickford’s wedding dress. But Greer and Banton got along famously. Paramount was doing well too, with its new star, the “It” girl Clara Bow and her jazz age movies. It helped that both designers were paid handsomely.

Travis Banton had just settled in when Howard Greer decided to open his own couture business in Beverly Hills. Greer left in 1927 and had an instant clientele of Hollywood movie stars. Travis Banton now became the Head Designer and Edith Head began designing the B pictures and “Horse Operas,” as she called the western movies. And as the roaring 1920s turned into the 1930s, new fashions developed and a new bevy of movie stars crashed through the Paramount gates.

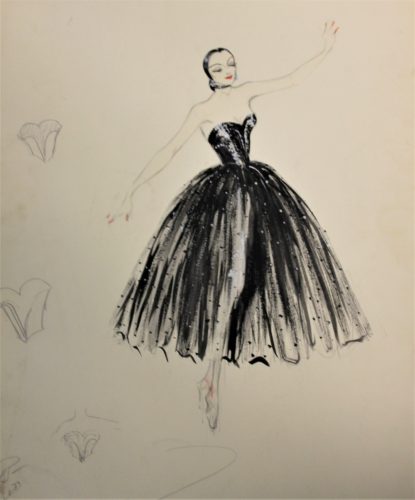

As big as the 1920s movie divas were at Paramount, the new stars of the 1930s proved just as bright and glamorous (and demanding). At the end of the 1920s the flapper look suddenly became passé . Even the popular uneven hemline (or handkerchief hemline as it was often called) became immediately out of fashion when Jean Patou in Paris came out with his long gowns and dresses in 1929. Banton’s design above for Lilyan Tashman in The Marriage Playground, 1929, was only shot from the hips up as a consequence. The new Parisian style affected all the Hollywood designers, and the studio moguls were not happy. From then on, Hollywood costume designers developed a “timeless” style of glamour and chic based on a look born in Hollywood movies.

Travis Banton’s special gift was to transform the excess of the 1920s into the fashionable glamour that became Hollywood’s hallmark. And with the new stars of Paramount, he had the models that would become famous around the world. The Depression audience needed a diversion – featuring exotic settings and stories of rags to riches. This became the new entertainment. And a new star came to Paramount in 1930 who became its answer to Garbo: Marlene Dietrich from Germany. She came via a film about the French Foreign Legion and a handsome legionnaire played by Gary Cooper. The film was Morocco. Period films had not gone away, however. In 1934 C.B. De Mille made a lavish Cleopatra with unforgettable costumes by Travis Banton, worn by Claudette Colbert. Their overt sexiness must not have pleased Ms. Colbert, however, who probably blamed Banton rather than De Mille for their key presence in the film.

The exoticism of the 1920s was replaced by the glamour of the 1930s. This glamour became the specialty of Hollywood, and Banton, Designers Adrian at MGM, Irene at Bullock’s Wilshire and also free-lanced, and Orry-Kelly at Warner Brothers were exporting the look around the world. Soon Claudette Colbert and Carole Lombard joined Paramount and Banton was dressing the A list of Hollywood. But not all was rosy. The demand to design newsworthy and glamorous fashions for demanding divas in their film roles on tight schedules was stressful. Banton’s relationship with Claudette Colbert deteriorated as she became very demanding about the look of her costumes. One day Ms. Colbert tore up his costume sketches because she didn’t like his designs. Banton was furious and disappeared for a week, drinking heavily the whole time. He was finally convinced to come back, but his days were numbered at Paramount. Edith Head took his place as Head Designer in 1938, but Ms. Colbert didn’t like her designs either. Ms. Colbert would use Irene to design her costumes after Edith Head’s Zaza (1938). But before Banton left, he had taught Edith Head to imitate his style of costume sketch illustration. It got so you couldn’t tell the sketches apart.

But just as Edith Head had taken over at Paramount, war had started in Europe. Foreign revenues for American movies was throttled and the importation of fine European fabrics came to a halt. Then, as the U.S entered WW II, fabrics were rationed. The days of glamour and lavish costumes were coming to an end. Edith Head believed that more realism was needed in her costume designs. Glamour and sexiness may still be needed for certain roles at certain times, but sparingly. She was probably as surprised as anybody, however, that her first big fashion trend was based on a costume for Dorothy Lamour based on an Indonesian sarong. Jungle Love from 1938, was so popular that several sequels followed over the next several years, all with Ms. Lamour in sarongs – or what passed as a sarong in Hollywood costume.

When the popular floral-pattern, printed fabrics were no longer available during the war, the fabrics were hand-painted at Paramount’s wardrobe department. Edith’s assistant hand-painted these floral prints and other fabrics as needed.

Except for Claudette Colbert, Edith Head was now designing the wardrobes for Paramount’s leading ladies: Betty Hutton; Veronica Lake; Barbara Stanwyck, and a mature Marlene Dietrich. As the 1950’s rolled in, she began designing for Gloria Swanson in Sunset Blvd., a legend from her very beginning days at Paramount. And then she designed for Elizabeth Taylor in A Place in the Sun released in 1951. Although she had illustrated her own costume sketches in the 1930s and early 1940s, she now needed a sketch artist in order to keep up. In her long career she would use several, including Adele Balkin, Rudi Gernreich, Waldo Angelo, Willa Kim, Pat Barto, Bob Mackie, Grace Sprague, and Richard Hopper. It was often through her sketch artists that Edith Head’s style became known visually in many magazine and newspaper articles and advertisements, and also through her costume sketches. Grace Sprague came along at the height of Ms. Head’s popularity in the mid 1950s – early 1960s. Ms. Sprague was so proficient and quick at illustration that she would turn out several variant sketches for the same costume based on Ms. Head’s idea.

Edith Head would occasionally have other costume designers work with her as well. Most of these designers worked on the C.B. De Mille films where he often used teams of designers. Natalie Visart was a regular designer working on the De Mille films, along with long-time De Mille designer Gwen Wakeling, Dorothy Jeakins, Elois Jennsen, John Jensen and Ralph Jester. Mme. Karinska, the Broadway costume designer and Raoul Pene du Bois also from New York joined the design staff in 1944 to work with director Mitchell Leisen on Lady in the Dark. Pene du Bois worked on six films until 1946.

Mary Kay Dodson a former model for Irene (of Bullock’s Wilshire) was also added to the design staff in 1943. Ms. Dodson was brought on to work with Mitchel Leisen. She was not only glamorous herself, but she proved to be an excellent designer. This caused Edith Head to grow jealous of the newcomer, who came to the studio dressed like a star and was given choice assignments. It didn’t help that while on location with Leisen making Golden Earings she doubled for Marlene Dietrich before Marlene could arrive. Apparently she was also dating a Paramount executive. She was given a five-year contract in 1942. Edith Head also became nervous when Mary Kay Dodson started getting good press in the Los Angeles newspapers and Hollywood columns. She must have been relieved when, at one of Lucille Ball’s parties, Miss Dodson met the New York playwright Jody Hutchinson. They eloped two weeks later on October 4, 1949 and they soon moved to New York where Ms. Dodson started her own line.

Edith Head did not need to worry about her longevity as a costume designer. She went on to win eight Oscars for Best Costume, a category which was finally instituted by the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts & Sciences in 1948. And she was nominated thirty five times. In all she worked on designing costumes for some one thousand films. Ms. Head dressed virtually all the great actresses of the era. She not only had great skills and talent, but she knew how to work with her movie stars to adapt her designs to their personalities and desires as well as the roles they were playing. Ms. Head was still the Head Designer at Paramount when Gulf & Western bought Paramount in 1966. In 1967 she turned 70 and feared that her contract would not be renewed. She took the opportunity to move to Universal Studios where Alfred Hitchcock was now directing films, with whom she had worked on several films. She remained at Universal until her death in 1981.

The studio system in Hollywood came to an end at the time Edith Head left Paramount. Costume designers were put on short term contracts and soon were free-lancing. The vast wardrobes of costumes and warehouses of props were often auctioned off in part or in whole. Studio ownership itself changed hands from corporation to corporation. The costumes and props that had been used as tools in the dream factories for decades, often discarded, suddenly became valuable memorabilia in the late 20th Century. Paramount, like some other studios, began to organize and archive its remaining artifacts and in 2007 launched its costume and prop archive. Archives manager Randall Thropp was able to answer questions about the archives for Silver Screen Modes.

- When were the Paramount Pictures Archives first established?

Paramount has always maintained some sort of film collection dating back many years. However, by the mid 1980’s the archival process fell into place. The current building was opened in 1990 and now houses every aspect of the Archives. The Costume/Prop Archive was started in 2007, but became official in 2009.

- When did you first become involved and what is your current role?

I started working at Paramount in the costume department in 2003. By the end of 2004 I was managing the rental floor. Whenever I had to re-stock or write up costumes, I looked for names inside the garments and set them aside – thus laying the groundwork for archiving key pieces. When the costume department was closed in late 2007, I was allowed to pull together anything that I thought was “historical” and to set it aside. Currently I am the manager of the Costume/Prop Archive.

- Do the Archives contain all types of materials such as objects, graphic materials, documents, as well as costumes?

The Paramount Archive is unique in that it covers many different areas under the direction of Andrea Kalas (SVP Archives). We have a team of people who oversee film preservation, restoration, stills, music, costumes, props and jewelry. Within the costume collection I also have 350 sketches and a collection of stills related to costume continuity. We are the only studio archive that has a jewelry collection. There are approximately 12,000 pieces dating back to 1923.

- Most studios have seen the loss of their material heritage through gifts, auctions or other means. What vintage do the various Archive materials represent?

There are 3500 vintage costumes dating back to 1914. The contemporary collection has over 29,000 individual pieces dating back to 1987. Sadly, there is a big gap in our collection for films between 1967 and 1986. Paramount is also the owner of the Republic Pictures catalog and a significant amount of work has been done to preserve and restore those titles. Our music and stills collection are quite extensive dating back to the silent era.

- Was going through the existing collection difficult and was it well supported by the Corporate HQ?

Our current management team could not be more supportive. They understand the historical value these elements represent. The Archive is also a very important stop on the V.I.P. Studio Tour. We have film fans from all over the world passing through and viewing the assets we have on display.

- Are the Archives in a separate facility or at the Melrose main lot?

The Archive is located on the lot – however we have several storage facilities off lot.

- Are the Archives accessible to researchers or the public?

The Archives is not publicly open generally to researchers like a library would be – our clients are the many departments of the studio officially. Research for example that is done by production is very welcome, but as I mentioned, the V.I.P. tours give the public a chance to see the artifacts.

- Costumes and textiles are fragile. Are they stored in boxes or through some other method?

The costumes are stored in various ways. Some in muslin bags, some in archival boxes – but many are in clear garment bags with archival tissue.

- Are there records still extent from the Paramount costume designers such as costume plots, production/star/costume cards, costume sketches, wardrobe test photos, etc.?

As I mentioned earlier – we have approximately 350 sketches dating back to the late 1940’s. The bulk of the sketch collection is from the 1950’s and early 1960’s. There are only a handful of continuity books from the older titles, but we do keep all the continuity books from our contemporary productions.

- What is the date range of the items in the Archives? Is there a cut-off date or are efforts made to archive new or newer materials?

- The oldest piece in the collection is dated 1914 and was owned by the director, William Desmond Taylor. Many of our 1920’s costumes were lost to neglect. (Silk chiffon and heavy beading do not like wire hangers and heat.) Also, as you know, many costumes that were considered “dated” were sold off by the studio as far back as the 1940’s. Today I work in tandem with Feature Production and go through all the assets from current productions. I determine what we put into the archive and what can be recycled into future productions. We also service Marketing and Publicity requests as well as museums all over the world.

- I would imagine Edith Head is well represented by costumes in the collection. Are there costumes you don’t have by some of the Paramount designers?

Edith Head is attributed to at least 75% of the vintage collection. We also have pieces designed by Travis Banton, Howard Greer, Mary Kay Dodson, Irene, Mitchell Leisen, Oleg Cassini and Raoul Pene Du Bois.

Yes, there are many costumes from the classic years that we are missing. I wish we had more Banton pieces, but I’m happy to have the few that we do.

- What are a couple of your favorite items in the collection?

I have many favorites including, Barbara Stanwyck from THE LADY EVE, Carole Lombard from TRUE CONFESSION, Barbara Stanwyck from DOUBLE INDEMNITY and Roy Rogers from SON OF PALEFACE. (all Edith Head)

As far as costumes from our contemporary collection I must single out LEMONY SNICKET (Colleen Atwood), BLADES OF GLORY (Julie Weiss), ALLIED (Joanna Johnston) and ROCKETMAN (Julian Day).

Thank you Randall Thropp and Andrea Kalas, Senior Vice President, Archives at Paramount Pictures.

MY FORTHCOMING BOOK:

Views: 2040