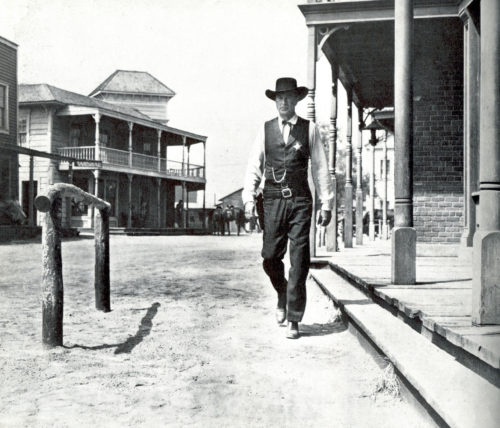

High Noon, the 1952 classic western starring Gary Cooper, directed by Fred Zinemenn and written by Carl Foreman, set the model for the lone hero standing up to a bunch of outlaws. Cooper played the part of Will Kane, the newly-married town marshall. He has just resigned to leave town with his bride, a pacifist Quaker played by Grace Kelly, and a new marshall will soon arrive. But so will outlaw Frank Miller who Kane previously sent to prison, but now set to arrive on the noon train. And Miller’s bringing three other outlaws to join him. The wedded couple are no sooner on the outskirts of town than the marshall says he must turn back and do his duty, his bride aghast. Yet he never thought of taking on the outlaws alone. But now his deputy leaves him out of spite and jealousy, and then his wife makes plans to take the first train out of town. He tries to deputize men in a saloon but none of them will budge. He goes to a church and asks for help, but the men just want peace and the mayor doesn’t want the bad image of a gunfight in the street. His mentor and the past marshal won’t help him, and he even gets in a fistfight with his now-drunk deputy before he resolves to face four gunslingers on his own. Walking out in the middle of the street, western-movie style, he shoots it out with them, killing one, then two, and with the help of his wfe who shot one, shoots the last one standing: Frank Miller. He tosses his tin badge to the dirt street and they leave town. The marshal has done his duty as the lone hero and can now ride off in the sunset, albeit he leaves with a wife in a wagon.

Shane quickly followed High Noon as another classic western, the two cementing the myth of the lone hero in western movies. Here Alan Ladd stars in the film directed by George Stevens and written by A.B Guthrie. The movie itself begins with Shane riding his horse into a family homestead. Shane is the only name he’s given, and as with almost all lone western heros, his past is mostly mystery. The plot is set up immediately, when the young boyJoey plays with and cocks a gun, Shane reacts instantly by drawing his pistol. The alarmed father, Joe, played by Van Hefflin, sends Shane away. No sooner is he gone than riders come up, one of which is a cattle baron named Ryker who tells the family they are squatters and to get off the land that he uses for grazing his cattle. Joe refuses and things get tense until Shane returns as back-up, and the cattlemen leave. Joe’s wife Marian played by Jean Arthur, urged by Joey (Brandon de Wilde), invites Shane to stay for dinner, and then Shane spends the night. He ends up staying a while and helping do some work. The homesteaders are being threatened all around the area and some are leaving. When Shane goes into town to get some work clothes, he is called a sodbuster, but resists getting in a fight. At a homesteader meeting the harrassment is talked about including Shane backing down, which Joey overhears. Then several homesteaders go to town for 4th of July provisions including Shane, and this time, he goes to the saloon and throws drinks into the cowboy that harassed him and gets in a fistfight and wins, and then takes on all the other cowboys and is joined by Joe as well. When Ryker offers him a job and he refuses, Ryker hires a notorious Cheyenne gunslinger, played by Jack Palance. But meanwhile not only does Joey admire Shane but so does his mother. Ryker visits them with his brother and gunslinger Wilson to say they were there first to pacify the land that Joe is on, and it shouldn’t have fences. He then offered to buy them out. Joe says the government recognizes the homesteaders’ land. But the Ryker bunch start getting violent with the others and have orders to deal with Joe too. One of the homesteaders is killed going into town, another’s house is burned down. Some homesteaders want to leave. Joe is fixing to go into town to take on Ryker single-handedly, but Shane and joe get into a fight and Shane knocks him out, with the thanks of Marian, but Joey now resents him. Shane goes in Joe’s place, and confronts Ryker, starting with gunslinger Wilson, and brother Morgan, in the classic saloon gunfight. With sidelines help from Joey, Shane avoided a trap. With scored settled and the smoke cleared Shane gets set to leave. Joey then says he was sorry for what he said and asks him to come back to the homestead. Shane says he doesn’t belong there. “A man’s gotta be what he’s gotta be.” “A brand sticks,” he adds, and “There’s no going back to the past.” As he rides off Joey cries out, “Come back!” But Shane is himself a gunslinger, and he has taken on himself the violence that was necessary for the settlers to lead a peaceful life. Throughout Joey was the character that validated Shane, through initial curiosity and fascination, then disappointment and even resentment, to active partnership and to final jilted but glowing admirer. We see Shane through his eyes – the lone Western hero. “Come back.”

The lone western hero is a powerful myth reinforced by a long line of western movies including The Searchers, Pale Rider, and The Good the Bad and the Ugly. The model has also influenced police and detective films of modern times. But the actual episodes that inspired these films belies the theme of the lone hero. In them we find the legendary lone hero is more myth than fact in that iconic period of the American West.

One of the most notoriuous episodes of the American West was the Johnson County war of Wyoming in 1892, also called the Wyoming Cattle War or simply “The Invasion.” It is infamous because the powerful interests of big ranchers and the state government they influenced suppressed the story for so long. Although it was the subject of the film Heaven’s Gate (excessively dramatized by Michael Cimino in a story that was dramatic enough), its story elements have been lifted and used, if not the full story itself, in many westerns. In the Johnson County war, homesteaders came and settled onto land that was also used by big ranchers to graze tens of thousands of cattle. This was the rich grasslands where buffalos, by then nearly extinct, had roamed for centuries. The settlers took up land where there was water, such as valleys along streams and rivers. They put up fences and raised livestock of their own. The big ranchers let their large herds of cattle roam free through the fall and winter, grazing as they went. When winter blizzards came the cattle drifted south, sometimes for hundreds of miles. By spring they would drift back to their native lands, joined by thousands of calves. This is when the “round-up” would take place, and the cowboys would brand the calves. Friction would arise over unbranded, “maverick” cattle, ending up in different herds, often with charges of “cattle rustling” made against the small ranchers or certain cowboys. Since the big ranchers and their Wyoming Stock Growers’ Association had laws written in the State legislature to protect their own interests (has nothing changed in 125 years?), the farmers and small ranchers found themselves perennialy on the losing side of whose cattle was being rustled.

Then as bad winters and more settlers came, and their fencing expanded, the profits of the beef cattle business sunk.The big ranchers decided to get more aggressive with the settlers. Not wanting to get physical themselves, they hired gunslingers from Texas and Arizona and other states, and outfitted them with guns and supplies in three supply wagons including dynamite. This was still the wild west as far as some were concerned.

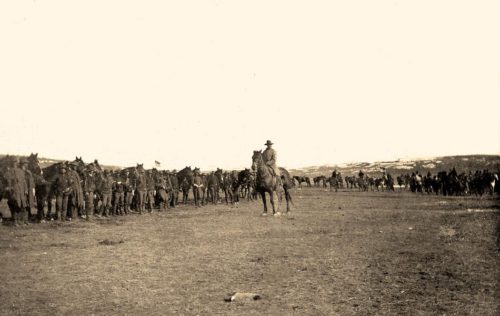

Twenty of the big ranchers and some 30 hired gunmen rode into Johnson County, having cut the telegraph lines so that no news could get out about what they were going to do. Two lynchings had already been committed, and a list was drawn of people to be killed. The armed group first surrounded the K.C. Ranch house where alleged rustlers Nate Champion and Nick Rae were staying along with two traveling trappers. The trappers were allowed to go when they went outside but they shot and killed Rae as he came out in the morning and had an hours-long shoot out with Champion, who was writing in his diary the whole time. As the day was ending they set fire to the house. Nate Champion was shot and killed as he fled. Jack Flagg and stepson were riding by and witnessed the events until they too were shot at. They high-tailed it to the nearest town of Buffalo to alert the settlers that the invaders had arrived. Meanwhile the self-satisfied invaders took their time, having a hearty meal before their own planned ride to Buffalo, where they intended to kill sheriff W.G. “Red” Angus. But Angus was no lone hero – some 200 settlers has signed up as his posse to fight off the gunslingers. As the invaders were on their way to Buffalo, they got word of the riled-up citizens – farmers and town-folk alike – and decided to take up a defensive position at the T.A. Ranch at Crazy Woman Creek. The ranch buildings were made of hewn logs and now to which the invaders added breast works and gun-slits, all under orders of the group’s leader Major Wolcott. Except that their four wagons of supplies had been captured by the settlers – including their dynamite. Within hours the settler posse and Sherriff Angus arrived and took up positions around the T.A Ranch, only to be fired at, and they returned fire. The settler bullets doing nothing against log walls, they started working on an idea conceived by Arapahoe Brown – build a moving fort – the “Go-Devil.” This device was built of two of the big supply wagons from the invaders, rigged together with lumber and built with a protective lumber wall in front. The whole could be rolled up close to the ranch fence and dynamite tossed at the ranch house until the invaders came out where they could be shot. This attack vehicle was within distance of being implemented when the U.S. Cavalry from Fort McKinney rode in.

The invaders surrendered to them, with the understanding of the sheriff and the settlers that the invaders be held at Fort McKinney for trial. The quick arrival of the U.S. troops was the work of acting Governor Barber, who had, with help of the two Senators from Wyoming, woke President Harrison to say that an “insurrection” was taking place in Johnson County and beseeching him for the order to dispatch federal troops to stop the fighting (and protect the big ranchers and invaders). As it turned out the invaders were transferred to Douglas and then transported to Cheyenne where they could get an “impartial” trial. The judge meanwhile charged Johnson County $100 per man/per day for upkeep, nearly bankrupting the County. The two trappers, witnesses to the murder of Champion and Rae, had been kidnapped and then bribed to tell a false story at trial. At the trial, the judge acquitted all the big ranchers and their hired gunmen. They were left to their own fates and ignominy. That the story is not better known is testament to the ability of the powerful linked to government and their ability to suppress not only justice but history.

This was not the only case of the people rising up against gunmen riding into town. When the Jesse James/Frank James and Younger Brothers gang and their associates rode into Northfield Minnesota to rob the bank in 1876, several of the townsmen got rifles and guns from the hardware store and started firing on the gang members waiting outside the bank, killing two of them. Meanwhile inside the bank the assistant cashier refused to open the vault and was murdered. During the gunfire outside, other staff ran out the back door. All the robbers stole was a bag of nickels, all the rest getting shot and wounded and killing a couple more town people. After their escape the Youngers and James split apart. But the locals formed posses and within a couple of weeks the Younger brothers were captured and imprisoned. The James brothers managed to escape.

These real-life episodes did not lead to the lone-hero myth that was developed in the classic movies of the early 1950s. This post-war period had already seen the rise and wain of film-noir, and the expansion of the American suburbs. There were other needs at work in this myth-building phenomenon. Certainly the old tales of gothic knights and leather-stocking frontiersmen had an effect, and the basic call of the wild and the free. But Americans needed to cope with the disappearance of the old west itself. Not only was the physical west rapidly changing, but the promise that it held was evaporating too. Had we paved and polluted paradise? The Western Hero myth was the savior myth. But with the 1954 western film Johnny Guitar directed by Nicholas Ray, the western hero had been completely suppressed. Here is the first ripple of the tidal wave of anti-hero films of our current era, western and otherwise. Our current ever-present dystopian movie plots are beyond the abilities of any hero to save, merely surviving is the goal. Now no ordinary hero can cope with the mayhem of modern times, exaggerated ten-fold in movie-madness. Now its up to super-heroes to save us, as they fight super anti-heroes, or is it the other way around? Regardless, the actual facts of the Johnson County war may not be well known, but its implications have become all too clear.

Views: 1557