An American in Paris was made in 1951 at the very peak of the Hollywood studio system and the pinnacle of Gene Kelly’s artistic career. It was the perfect blend of art and technique in classic American movie-making. MGM had among its employees all the veteran craftspeople and artists that could produce such a film. And as with many great movies, the back-story is as fascinating as the movie itself. In 1950 as the first plans were being made for the film, MGM, and indeed the entire Hollywood film industry, was in transition. Television was siphoning off viewers and a court-imposed consent decree required studios to sell off their movie theaters. Cost-cutting was now the mantra, and MGM’s expensive musicals were not viewed favorably by its new production head Dore Schary nor by the corporate offices at Loew’s in New York. The old lion Louis B. Mayer, still in charge of studio operations, supported musicals and the planned An American in Paris, but it took a lot of pleading and persuasive pitches to gain the approval of Schary, and then even more to Loew’s corporate head Nick Schenck and his board. And still the threat of budget cuts loomed over the entire production.

An American in Paris was made in 1951 at the very peak of the Hollywood studio system and the pinnacle of Gene Kelly’s artistic career. It was the perfect blend of art and technique in classic American movie-making. MGM had among its employees all the veteran craftspeople and artists that could produce such a film. And as with many great movies, the back-story is as fascinating as the movie itself. In 1950 as the first plans were being made for the film, MGM, and indeed the entire Hollywood film industry, was in transition. Television was siphoning off viewers and a court-imposed consent decree required studios to sell off their movie theaters. Cost-cutting was now the mantra, and MGM’s expensive musicals were not viewed favorably by its new production head Dore Schary nor by the corporate offices at Loew’s in New York. The old lion Louis B. Mayer, still in charge of studio operations, supported musicals and the planned An American in Paris, but it took a lot of pleading and persuasive pitches to gain the approval of Schary, and then even more to Loew’s corporate head Nick Schenck and his board. And still the threat of budget cuts loomed over the entire production.

This post is part of Silver Scenes’ MGM Bologathon. My post on An American in Paris was previously published in 2012 as part of the Gene Kelly Centennial Blogathon.

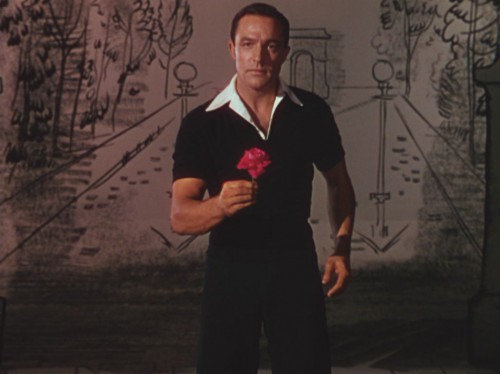

his own image or in his ability to produce a self-portrait, which he will soon to deface

The decision by Freed, Minnelli, and Gene Kelly to include a 17 minute long dance sequence was bold and risky. Regardless of the success of The Red Shoes, nothing of that scope had been done in an American film. Further, the ballet was to be a realization on film of the artistic works of Impressionist and Post-Impressionistic painters. This feature would not only guide the nature of the choreography, but also of the set designs, cinematography, action sequences, and costumes. The ballet scene would be the heart and soul of the film. The music, of course, would be based on the haunting score of George Gershwin’s An American in Paris symphony, with the story for the film by Alan Jay Lerner.

Other than Gene Kelly, the question of who should be cast for An American in Paris was not apparent. While MGM had several great female dancers, Kelly was convinced that a fresh faced and a native Frenchwoman should be cast as Lise Bouvier. And for that role he had seen a 19 year old French ballerina named Leslie Caron that he wanted for the part. This too was a risky move – a major role for a young woman who had never acted. In continuing with the relatively unknown cast members, Georges Guetary, a French Music Hall singer, was cast as Henri Baurel. For the fellow American expat and starving musician-neighbor, the inspired choice was the concert pianist and wit Oscar Levant, playing the role of Adam Cook. Another fortuitous decision was bringing in costume designer Irene Sharaff. Sharaff was a Broadway designer but had worked for a spell in Hollywood. Minnelli convinced her to come back from New York to design some 300 costumes for the ballet. While working on the costumes, Sharaff also started designing sketches for what the sets might look like for the various artist-inspired scenes. These sketches in fact were adapted by art director Preston Ames for the sets, which Ames, a former architecture student in Paris, could quickly envision. The sets would be based on the styles of Raoul Dufy; Henri Rousseau; Piere Auguste Renoir; Maurice Utrillo; Vincent Van Gogh; and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Not a bad set of artists from which to draw inspiration. But how would the ballet transition from one artist-styled set to the next?

Those transitions indeed became a high-point in Hollywood film arts and crafst.Some 30 painters worked six weeks to paint the backgrounds and sets. Irene Sharaff also came up with the idea of using certain dancers, characters she called Furies for the women and Pompiers for the men. The Furies were dressed all in red ballet outfits and the Pompiers were dressed as traditional French firemen, with their brass helmets but also adorned in a military-inspired costume. Together they served as the “bridge” from one scene to the next, luring Kelly as Jerry Mulligan to pursue the ever-escaping Caron as Lise Bouvier. These transitions were also accomplished by using a “match-cutting” filming technique whereby the action of the dancer is exactly matched from the end of one scene to the beginning of the next.

As the film opens, each character as played by Gene Kelly, Oscar Levant and Georges Guetary narrates that the happy characters depicted on screen, “are not me.” Gene Kelly as Jerry Mulligan is a struggling artist that stayed in Paris after WWII. He sells his paintings (sometimes) on a street in Montmartre, where a rich widow discovers him and decides to support him (with strings attached). Oscar Levant as Adam Cook is a struggling pianist, the “oldest former child prodigy.” In a very clever later scene Levant as Cook fantasizes about playing in a symphony, which he is also shown conducting while simultaneously playing several instruments. This take-off of an old Buster Keaton film is still funny, especially since Levant being the only one that truly appreciates himself, also fills the audience with himselves. Georges Guetary as Henri Baurel is the successful singer and entertainer, now worrying about getting older, but providing the yet unknown rival for the love of Lise. His singing performance of “I’ll Build a Stairway to Paradise”, in classic Hollywood show-girls-down-the-stairs style, is a highlight of the movie.  A later dual number of Kelly and Guetary in “S’Wonderful,” where they are still ignorant of their rivalry, is pure joy. But Kelly as Jerry Mulligan is deeply in love with Caron as Lise Bouvier, made beautifully obvious in the “Our Love is Here to Stay” number, their song and dance on the banks of the Seine, here amazingly duplicated on a painted set built around one of the those old MGM “cycloramas” is pure joy. Another scene provides laughs as Levant, sitting between Jerry and Henri while they each describe Lise and how much they love her, oblivious of each other’s common object of affection, all the while nervously smokes two cigarettes and chugs several coffees and whiskies.

A later dual number of Kelly and Guetary in “S’Wonderful,” where they are still ignorant of their rivalry, is pure joy. But Kelly as Jerry Mulligan is deeply in love with Caron as Lise Bouvier, made beautifully obvious in the “Our Love is Here to Stay” number, their song and dance on the banks of the Seine, here amazingly duplicated on a painted set built around one of the those old MGM “cycloramas” is pure joy. Another scene provides laughs as Levant, sitting between Jerry and Henri while they each describe Lise and how much they love her, oblivious of each other’s common object of affection, all the while nervously smokes two cigarettes and chugs several coffees and whiskies.

A later scene is the wild Beaux Arts “Black & White” Ball, here providing a stark contrast to the disintegrating relationships of the two couples: Jerry Mulligan with patroness Milo (Nina Foch), and Henri with Lise. Henri even overhears Jerry and Lise’s tender, heart-breaking exchanges.

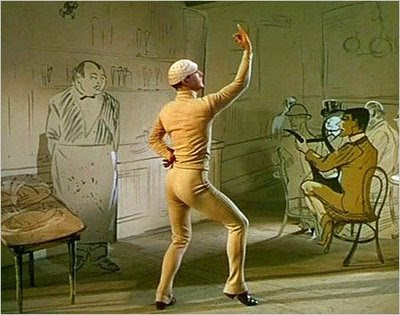

Forlorn, Jerry realizes he is just a failed artist, a stranger in a strange land. The ballet scene begins with Jerry sketching the scene of the Cheveaux de Marly, the sculpted horses flanking the Champs Elysees. He enters that sketched scene which is his ballet dream, the love of Lise symbolized by a fallen red rose. The ballet sequence will put to music and art all his hopes and fears, as he continually pursues Lise through various sets.

The opening scene in the style of Raoul Dufy’s Place de la Concorde becomes Jerry’s dream world.

The Furies, dressed in white and then red, beckon Jerry to pursue Lise. Gene Kelly as Jerry is dressed simply in form-fitting clothes, the better to appreciate his dancing and his physique.

The white furies turn to more intense red furies

The fountain at the Place de la Concorde serves as the dream dance floor to a united Jerry and Lise, dancing to George Gershwin’s exhilarating and romantic An American in Paris symphonic poem.

Jerry pursues Lise to the floral backdrop inspired by Pierre Auguste Renoir, and as they dance, they hold the red rose of love.  Alas, even in dreams our dreams escape us. Lise has been transformed into flowers, soon to fall from his grasp.

Alas, even in dreams our dreams escape us. Lise has been transformed into flowers, soon to fall from his grasp.  The background has now turned into the melancholy monochromatic artwork of Maurice Utrillo. Gershwin’s music is also changing to American jazz-inspired melodies.

The background has now turned into the melancholy monochromatic artwork of Maurice Utrillo. Gershwin’s music is also changing to American jazz-inspired melodies.  Jerry becomes homesick, as had Gershwin in Paris, which inspired him to add the sounds of American blues and jazz into his musical composition.

Jerry becomes homesick, as had Gershwin in Paris, which inspired him to add the sounds of American blues and jazz into his musical composition.  Jerry’s homesickness is symbolized by his former side-kicks, the U.S. military service-men shown in the scene. They are not quite tangible, the artist’s paint still fresh on their uniforms.

Jerry’s homesickness is symbolized by his former side-kicks, the U.S. military service-men shown in the scene. They are not quite tangible, the artist’s paint still fresh on their uniforms.

The scene turns to the artwork of Henri Rousseau: primitive; wild; and exuberant. Jerry’s service-men are now in dressed in cheerful suits, as is he, with the Pompiers now leading them forward in dance. And now Lise will reappear.

Here now we enter the more turbulent world of Vincent Van Gogh, the skies of the backdrops painted in swirled colors.

Here now we enter the more turbulent world of Vincent Van Gogh, the skies of the backdrops painted in swirled colors.

Only this dream turns into his real dream, and Lise returns, running up the stairs of the real (set) stairs of Montmartre. The final kiss says it all, our love is here to stay.

The film ends with a title card stating: Made in Hollywood, California. And so it was, where it also received 8 Academy Award nominations and won 6, though none for Minnelli. It won for Best Costume Design for Irene Sharaff, Orry-Kelly and Walter Plunkett. Yet Walter Plunkett, who designed the costumes for the Black & White Ball scene, must have found it ironic, he who had designed Gone With the Wind, the two Little Women ( and the subsequent Singing in the Rain, Diane, Raintree Countee), among scores of others. This would be his only Oscar, given for a relatively minor designing job.

Today it’s Singing in the Rain that is the crowd favorite and receives the “best musical ever made” accolades. No doubt that Singing in the Rain is the most cheerful and fun movie there is to watch, and the dancing is also outstanding. An American in Paris seems to be considered somehow less worthy because it strove to be art. But there is no more beautiful film ever made, and its integrated combination of music, dance, art, costume, and cinematography is the pinnacle of classic Hollywood film, and a proud achievement of the MGM Studio.

Views: 3458