There are times in history when creative geniuses cause shifts in the arts. It is very rare when such a person can cause explosive aesthetic changes in several artistic media such as set design, ballet, costume, fashion, and ultimately, the styles of Hollywood film sirens. This person was Leon Bakst, born Lev Rosenberg, a Russian painter turned set and costume designer for Sergei Diaghilev and his Ballets Russe, where his sensual and sensational designs shocked the audiences. In working with Diaghilev, who assembled a “dream team” of artistic talent,” these arts themselves were changed.

In the classical world of ballet, allied with symphony orchestras in entertaining high society audiences, the modernism and naturalism of Diaghilev’s ballets must have seemed revolutionary. The look was created by Bakst, the artistic director. His costume designs on canvas and backdrops combine Art Nouveau and Fauve styles, blended with Orientalism. The finished costumes presented a rush of colors, with incredible pattern and detail, the whole complementing the scenery and the new dance styles, music and choreography.

In Russia Diaghilev and Bakst had known each other before they were involved in ballet, having been part of the same art circle in college called the Nevsky Pickwickians. But it was in Paris that the Ballets Russes was formed, with Russian dancing luminaries Anna Pavlova, Vaslav Nijinsky, Tamara Karsavina, and Ida Rubinstein, and choreography by Michel Fokine. With classically trained Russian dancers, Diaghilev and Bakst would integrate the arts into the total ballet experience – music, dance, sets and costume – and with male as well as female dancers in prominence. The Ballets Russe began with some Russian tales and music , but with Cleopatre in 1909, Bakst’s second ballet, the full panoply of his artistic talents blossomed in conveying the story. Ida Rubinstein played the role of Cleopatra, and her provocative costumes shocked the audience. They would set the standard for all future Cleopatras of the silver screen.

A future patroness of Bakst, the American Warder Garrett wrote to her sister in 1915, “I go almost every day to pose for Bakst . . . he is one of the most strange human beings I have ever known.” Years later she would be his art representative in the United States. His vivid imagination was clearly translated onto the the page and the stage, but, under the costumes, he was fully aware that it was the body that animated the design.

The Bakst- designed costumes featured gold, lapis blue, malachite green, pink, orange and violet colors for the ballerinas and were very revealing through sheer fabric.

Scheherazade was produced by Diaghilev in 1910, with music by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov with set and costume design by Bakst. The setting was ancient Persia, with a story of Harem women, eunuchs and palace slave lovers. The ballerinas were costumed in sheer silk harem pants, the men in embroidered velvet in jeweled colors. Nijinsky appeared in gold body paint, dancing sensually with Ida Rubinstein as the corps de ballet moved in a controlled frenzy, their bold colored costumes contrasting with the red carpet and green walls.

Harem pants became a style sensation for women, especially after fashion designer Paul Poiret added them into his line the following year. They were considered very bold dress as both a form of trouser and with a foreign origin. The style worn in public was not however the diaphanous ones seen at the Ballets Russe.

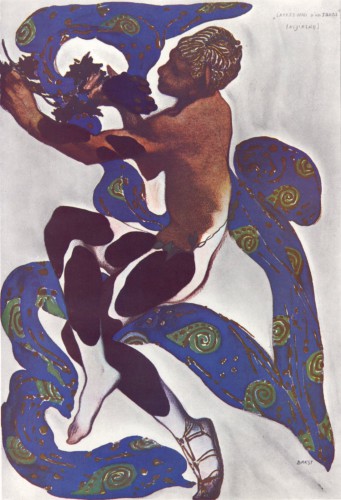

The ballet Dieu Bleu (Blue God) was produced in May 1912, with a libretto by Jean Cocteau and Federico de Madrazo and music by Reynaldo Hahn. The story is set in mythical India, where a couple visiting a shrine stirs local monsters, but supplicates the Blue God, or Krishna, to save them. Nijinsky plays the Blue God, wearing blue makeup. Bakst designed the costume below, thankfully saved and preserved at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra, along with many other costumes and artifacts from the Ballets Russes. Its skirt represents a lotus flower, with gold thread and embroidered with arabesques. The bodice was in pink and blue colors, with gold thread forming rays.

In 1912 one of the most innovative, but also disruptive ballets was produced by the Ballets Russes: L’apres-Midi d’un Faune (Afternoon of a Faun. based on a poem by Stephane Mallarme, with music by Claude Debussy, and choreographed by Nijinsky himself. This was not done by the usual choreographer Fokine, which he was unaware of. Nijinsky and Diagilev used as a theme the stylized art viewed on ancient Greek vases in the Louvre. Nijinsky’s dancing itself would be stylized and very profile-based, and most-shockingly, would use an erotic theme of a faun among a group of nymphs, this symbolized by the faun’s fetishistic attachment to a nymph’s veil, which he lies on dramatically to conclude the ballet. The ballet itself received mixed reviews and was controversial, but can be considered the first true modern ballet. Fokine resigned after his exclusion from doing the choreography.

In the ballet Nijinsky did not dance, he moved across the stage in stylized body configurations.

The Ballet Russe’s Daphnis et Chloe opened two weeks after L’Apres Midi d’un Faune, but with Fokine’s resignation, closed after two performances.

The costume design by Bakst for Daphnis et Chloe was made for a ballet based on a classical Greek mythological story. The costume design above influenced the silhouette of contemporary female fashion itself.

Paul Poiret was a leading French couturier in the first two decades of the 20th century, His move away from the corseted figure, his hobbled skirts, and his strong orientalism were influences from the Bakst costume designs. From Poiret and the Ballets Russe themselves, the fashion influence radiated from the upper-class spectators and the “beau monde.” Even Lady Sybil in Downton Abbey wore harem pants during the show’s first season in the period of 1912.

And it was not long before the exotic look of Scheherazade, Cleopatra, and other characters of the Ballets Russe were considered the models for dress and comportment for Hollywood vamps and movie stars.

Even though Travis Banton did not design this bat-winged hostess gown for Evelyn Brent until 1930 for Slightly Scarlet, it reflects the influence of the Bakst style from the Chloe design above.

The image below shows Alla Nazimova in SALOME, with costume design by Natasha Rambova, 1923. Nazimova was a Russian actress, The multi-talented Rambova was an American that assumed a Russian name. The vivid costume and setting shows the influence of the Bakst designs.

Pola Negri starred in her first American film in 1923: Bella Donna. She would become a leading vamp and rival to Gloria Swanson at Paramount Pictures. Her costumes were designed by Howard Greer, who was very fashion forward.

Another Russian had made waves in early 20th-century fashion design, Erte, (French for R and T) the name used by Romain de Tirtoff. Erte moved to Paris in 1910 and worked as a designer for Paul Poiret, and used a Bakst-influenced Orientalism in his fashion designs. He was also a fabulous illustrator, and regularly illustrated the covers of Harper’s Bazaar with his fashion illustrations. In 1925 he was hired by Louis B. Mayer to become a costume designer at M-G-M, where Erte’s studio was replicated on the studio lot. Erte designed for films such as Ben Hur, Paris, Dance Madness and The Restless Sex. He never fit in to the studio system of hurried costume designing, and when Lillian Gish complained about the unrealistically lavish designs she was getting as a street girl in La Boheme, he quit. His influence on Hollywood’s young costume designers had already been long established.

Bakst had made inroads into Hollywood in other ways. Director and producer Walter Wanger had met Bakst and Nijinsky when he was a college student at Dartmouth. He had been very impressed by them and was influenced by Cleopatre and the Ballets Russe. “I am very fussy about clothes and sets,” he wrote in 1949. In 1939 he told a reporter that the Ballets Russes “…. were the greatest influence on drama, direction, lighting, costume designing, and interior decoration in the last fifty years.” Walter Wanger produced the 1963 Cleopatra and cited Bakst as an influence on its design.

Diaghilev continued to produce the Ballets Russes until his death in 1929. He involved many leading figures of modern art in their productions. Picasso and Miro designed sets or costumes, along with Coco Channel. Satie, Ravel and Stravinsky composed or conducted music. But like Julian Craster in The Red Shoes, or like Paul Grayson in Flesh and Bone, Diaghilev was jealous and controlling, Years earlier When Nijinsky married Romola de Pulszky, Diaghilev dismissed him in 1913 (Diaghilev and Nijinsky had been lovers). The year before, Bakst had begun designing costumes for Ida Rubinstein, who had started her own ballet company. Diaghilev dismissed his old friend too.

It is hard to imagine the impact that the Ballets Russe had on its era. Probably the closest equivalent would be that of the Beatles, although the ballet had a more narrow yet very deep audience. It is regrettable that its time came before film and sound recording could adequately capture its art forms.

Views: 391