He went by the stage name of Orry-Kelly. Designers liked using just one name at the time. But he was born Orry George Kelly in Kiama Australia. His friends just called him Jack. He dressed the top movie stars of the Golden Age of Hollywood, from Bette Davis to Marilyn Monroe. He was a hard drinker with a temperament more suited to that of a big movie producer. He wrote his memoirs – which were never published in his lifetime. In fact they sat in drawers and boxes for decades – until 2016. Orry-Kelly had been room-mates with Cary Grant, both in New York when Cary was still named Archy Leach, and then in Los Angeles. They had a falling out subsequently, and It was rumored that Grant blocked publication of the memoir. At any rate, the book Women I’ve Undressed, by Orry-Kelly but ghost-written by Whitney Stine when Orry-Kelly was still alive, has now been published in Australia and in the United Kingdom. It seems U.S. publishers care less about our own Hollywood heritage. The book has also been turned into a docu-drama directed by Gillian Armstrong.

Kiama Australia was a small seaport town. His mother was a housewife and his father was a tailor. The young Orry developed his future passion when his mother took him to the theater in Sydney when he was seven. He loved the experience and the next Christmas he got a miniature theater as a gift. He made his own sets and actors, which he dressed with scraps from his mother’s leftover materials. His father told him boys shouldn’t be playing with dolls and one day destroyed the whole set.

As an older youth Orry moved to Sydney to attend technical school, at first living with his aunt but eventually going out on his own. Although he got a job in a bank, he hung around the theater looking for parts, with a few minor roles on stage coming to him. But It wasn’t long before he was mixing with a rough crowd of pick-pockets and prostitutes. Realizing he was only going to get in trouble he decided to move to New York.

Once in New York, he found a hotel room and looked for parts in vaudeville. His neighbor and friend was Gracie Allen, who would soon partner with George Burns. Another friend-to-be in the area was Jack Benny. And then sharing his room was another recent arrival to New York, struggling vaudevillian Archie Leach. Although this was during the Prohibition, the heavy drinking that Orry-Kelly got used to in Sydney continued to be a regular habit. Orry-Kelly had auditions and some performances, he just never made a success on the stage. So in order to make ends meet he turned to his artistic abilities. He painted some murals and experimented at home hand block-printing his designs on shawls, and selling the best ones on the street. He found a way to print his designs on ties also, and got Cary Grant to both make them and sell them on a 50-50 commission. Soon they were able to support themselves without the theater. But then he got a job designing costumes for the Schubert Theater. He even designed Katharine Hepburn’s costumes for Death Takes a Holiday, though she only lasted a week in the role.

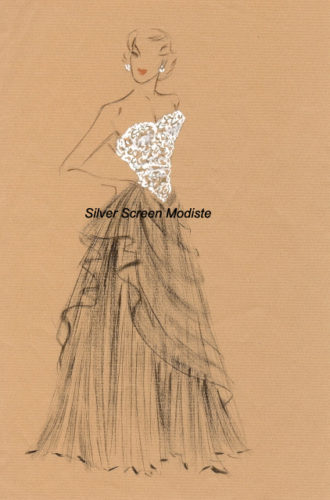

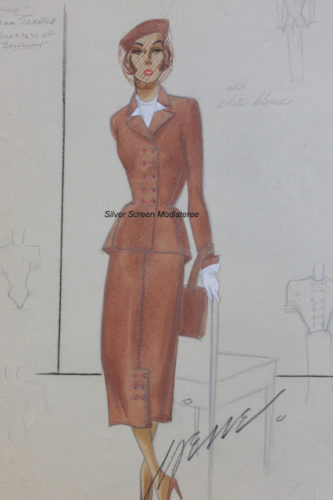

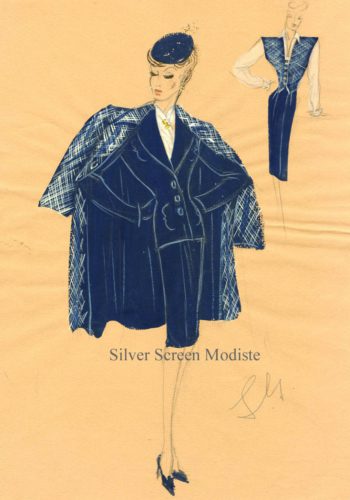

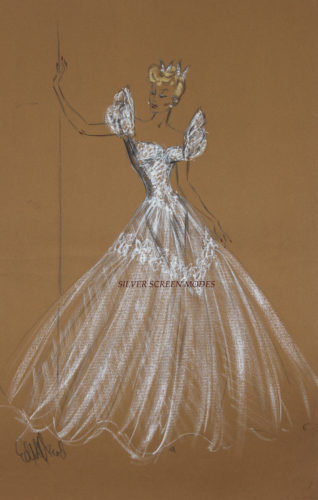

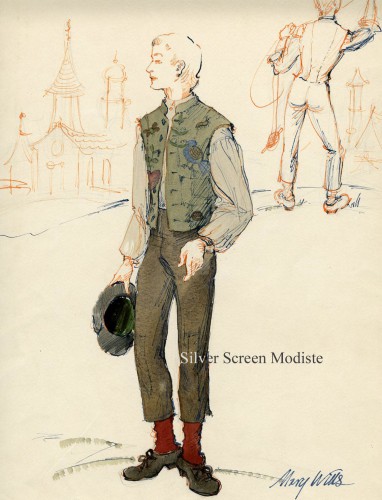

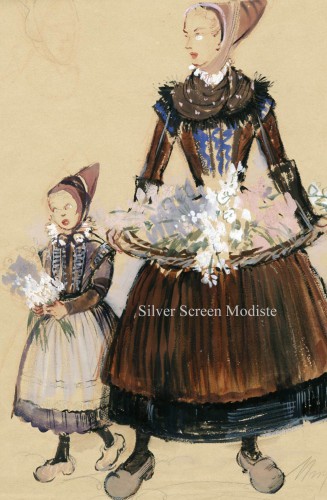

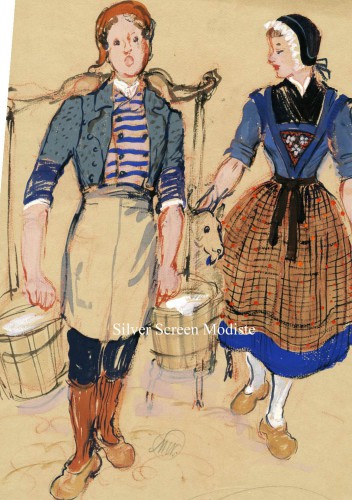

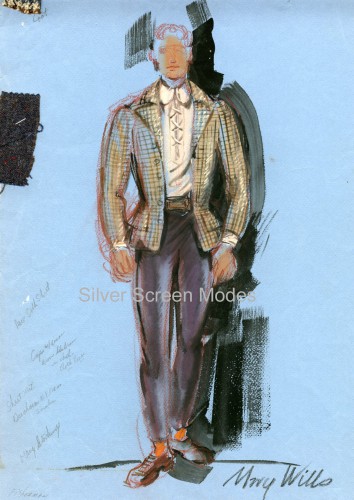

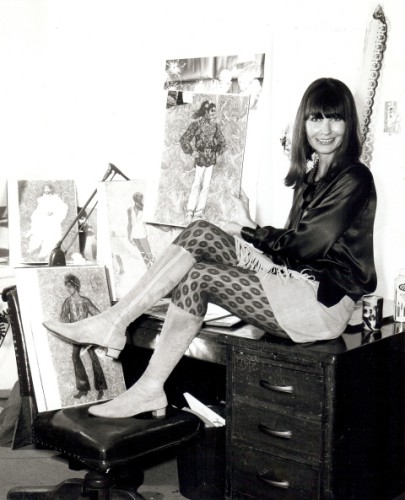

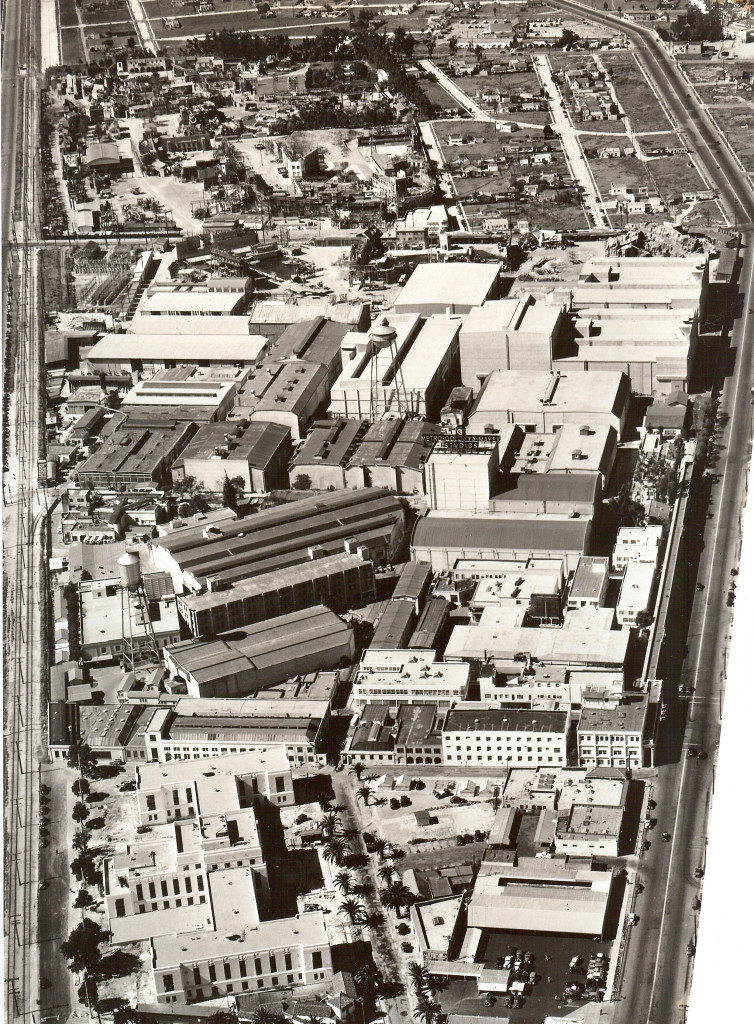

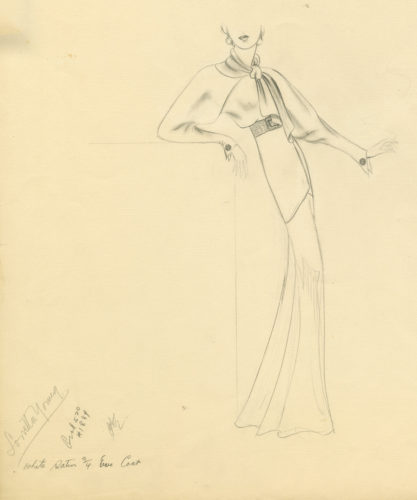

Orry-Kelly was broke by the time he made it to Los Angeles in 1931. Archie Leach came separately and got a screen test and then a contract at Paramount, along with the new name of Cary Grant. They met every night for a 65 cent dinner at the drug store counter- splurging for the 85 cent version on week-ends. Cary’s agent took Orry-Kelly and his portfolio for an interview at Warner Brothers. After waiting 42 days he finally got a job offer as costume designer. He said in his book that his first movie designs were for Loretta Young, who he loved working with. This was for Week-End Marriage in 1932, Then he designed the costumes for Bebe Daniels in Silver Dollar, a period film about the Silver Queen of Denver, Baby Doe. I include below several images from my own costume sketch collection.

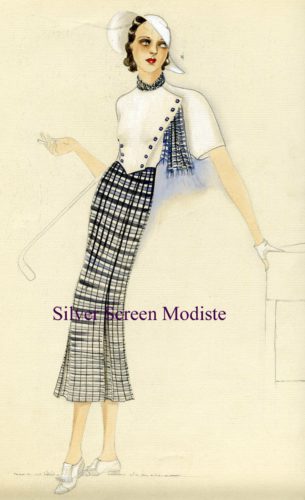

Above is my costume sketch of Orry-Kelly’s design for Loretta Young in “They Call it Sin,” 1932.

Above is my costume sketch of Orry-Kelly’s design for Loretta Young in “They Call it Sin,” 1932.

His first designs for Kay Francis, the fashion-plate of Warner Brothers, was for One Way Passage. He said she was, “Well mannered, cooperative, easy to please, and knew exactly what she wanted.” Boy was he in for a rough ride with some of his other assignments.

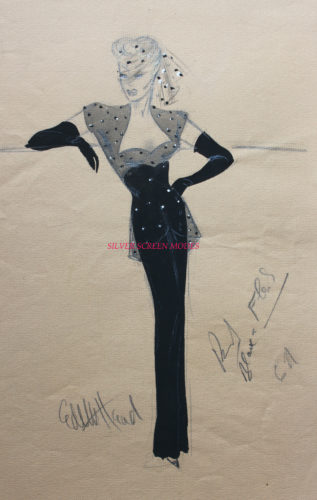

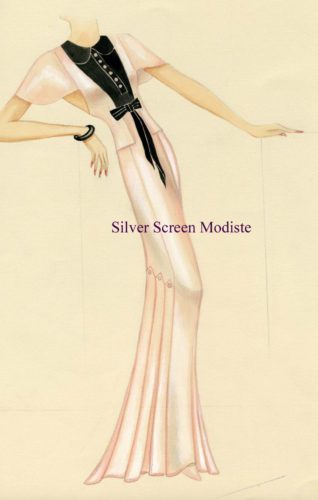

Orry-Kelly said when he first got to Hollywood he studied the work of the top two designers: Adrian and Travis Banton. But in order to be different, he decided to design “simple, unadorned evening gowns.” The good news was Warner Brothers was picking up his contract – for $750 a week – and he could establish his own style as the Warner Brothers style.

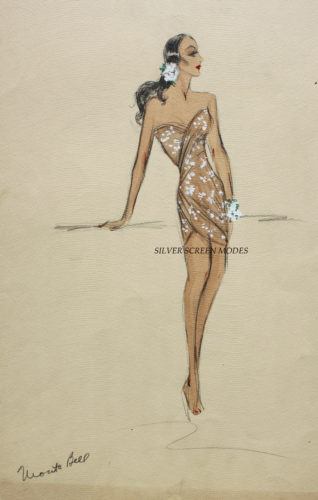

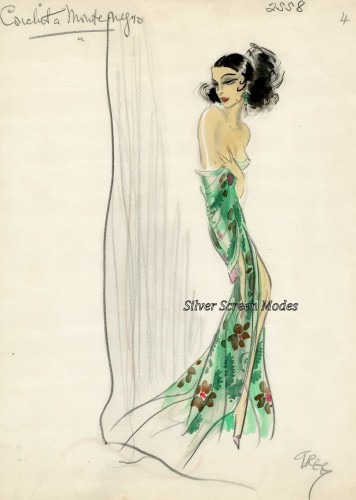

Orry-Kelly reminisced about the first time he dressed Dolores Del Rio, star of films Wonder Bar, Madame du Barry, and In Caliente. “I draped her naked body in jersey. She wanted no underpinnings to spoil the line. When I finished draping her she became a Greek goddess as she walked close to the mirror and said, ‘it is beautiful.’ Gazing into the mirror she said in a half-whisper, ‘Jesus, I am beautiful.'”

Musicals had become a specialty at Warner Brothers ever since they brought in sound movies. The early 1930s was also the era of Busby Berkeley and his big chorus-girl musical numbers. Orry-Kelly worked with Berkeley on such hits as 42nd Street and Gold Diggers of 1933. They would often go out drinking after the day’s work, and one night ended up at “Madam” Lee Francis’ and her girls’ establishment. Lee told him later that he was the sole representative of the designers who became a patron.

Orry designed for Ginger Rogers in her small roles in 42nd Street and Gold Diggers of 1933. In his book Orry Kelly states that subsequently it was Irene and then Jean Louis that dressed her. He had mis-remembered this, as Walter Plunkett dressed her at RKO, and then Bernard Newman.

Orry-Kelly became so busy at Warner Brothers that at one point he no longer painted the faces for his costume sketches.. And in fact he quit painting the costume sketches at all in favor of just doing pencil sketches. The otherwise beautiful costume sketch for Helen Vinson above in The Little Giant, co-starring with Edward G. Robinson, has no face. The costume sketch below for Loretta Young is done just in pencil. He designed for 23 movies in 1932 when he started, but in 1933 he did 42.

Bebe Daniels was already a big star by the time Orry-Kelly got to Hollywood. One of his first jobs was designing her costumes for Silver Dollar, a period film. His next designs for her was for the big musical, 42nd Street. Although Ruby Keeler stole the show, the best costumes went to Bebe Daniels, including the outfit below. It was worn in an important scene with George Brent. The fox furs were eliminated, which was indicated at right on this sketch.

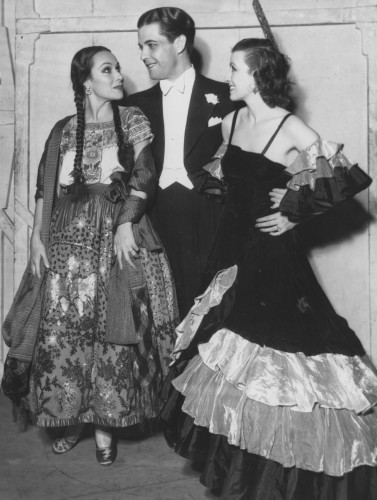

Orry-Kelly led an active social life with the Hollywood social set and celebrities. He remembered one of Marion Davies’ costume parties in Malibu, this one with a Spanish theme. Some of the guests included Dolores Del Rio, Carole Lombard, Constance Bennett, Jean Harlow, Marlene Dietrich, Hedy Lamarr, Eleanor Boardman, and Ann Warner (Jack’s wife), among others.

Ann Dvorak was another beauty at Warner Brothers, whose flame did not last long enough. Orry-Kelly’s fashionable outfit design for Midnight Alibi is shown below.

Although he had been working with Bette Davis for many years, the two temperamental artists could occasionaly get into tifts. While working on Now Voyager, Bette Davis was in a bad mood for a whole week and wouldn’t look at any of the three gowns Orry-Kelly had prepared for her fittings. This caused him to drink even more than usual and get in a bad mood himself. Finally Bette tried on two of them which she wore in the film. One is shown in the photo below.

Casablanca is one of the most favorite films of all time. Orry-Kelly designed the women’s wardrobe including Ingrid Bergman’s day dress shown above. The white sleeveless top and skirt with the striped short-sleeved sailor sweater was a big fashion hit in 1942.

Orry-Kelly claims he designed the costumes for Lauren Bacall’s first movie, To Have and Have Not, which paired her with future husband Humphrey Bogart. Milo Anderson got the design credit for the film and was likely the designer. This was the role where she said, “You know how to whistle don’t you Steve? You just put your lips together and blow.”

After a brief period in uniform during World War II, Orry-Kelly himself got in a tiff with Jane Wyman and one of the producers in one of her films. After that he left Warner Brothers and went to 20th Century-Fox on a non-exclusive contract. Jack Warner told him he would double his money. Bette Davis had wanted him to design her costumes at 20th Century-Fox for Dark Victory – he did for $2000 a week, triple his WB salary.

He also designed films at Universal including those for Shelley Winters, who he couldn’t stand working with. This was during her brief sex-kitten days. He didn’t renew his contract at Universal. He later had to dress her again for a Daryl Zanuck production. Although he doesn’t relate this in his book, it’s been told that at one point Shelley Winters refused to come out of her dressing room trailer for a costume fitting. Orry-Kelly got so mad he rocked the trailer back and forth until the terrified Winters ran out.

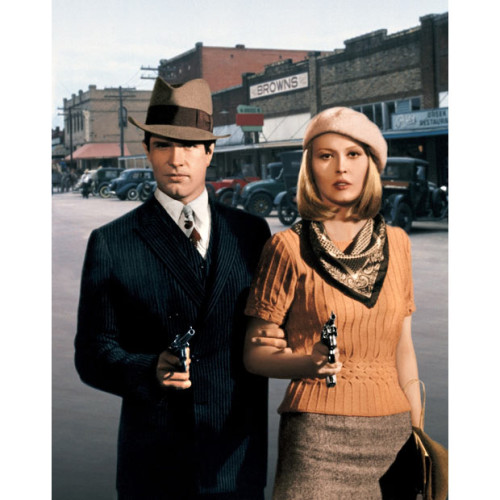

Orry-Kelly had always wanted to dress Marilyn Monroe. He thought she had always been put in gowns and dresses that were too tight, and should be dressed in bias-cut satins that just draped her figure. When the film Some Like it Hot was announced, he asked Billy Wilder for the costuming job and got it. But Orry-Kelly was surprised when he first saw Marilyn in a meeting. She had gained weight (she was pregnant during part of the filming). He knew he would be dressing her along with Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon in a scene together where the two men were dressed as women. He selected a matt finish fabric for her skirt and a more shiny fabric for theirs, he told her, so as to make her rear not look as big since the men’s were naturally smaller. At this she took offence and was cold to him the rest of the time. Tony Curtis gave a different story. He said he and Jack Lemmon were getting measured by Orry-Kelly, just like Marilyn Monroe was. When Marilyn got measured, “He put the tape around her legs, looked up at Marilyn and said, ‘You know Tony Curtis has a better-looking ass than you.’ She was standing there, she unbuttoned her blouse and said, ‘He doesn’t have tits like these.'”

One film that Orry-Kelly narrowly missed doing was My Fair Lady with Audrey Hepburn. The director George Cukor wanted him for the film and so did Warner Brothers. But Cecil Beaton was specified in Alan Lerner’s contract, so Orry-Kelly lost out. Beaton’s costumes for the film have been sanctified by time, but I think Orry-Kelly would have done an even better job. He tells many anecdotes in his book, and relates stories about other famous actresses he dressed, including Ava Gardner, Rosalind Russell, Rita Hayworth, and Natalie Wood.

Orry-Kelly died of liver cancer in 1964. Now with both the book and the film out on Orry-Kelly, and an exhibition that was held in his native Australia, he is justly being celebrated in the English commonwealth. If only we could have such triple crowns for some of our American film costume designers.

Views: 1366