Early and silent films are known to have low survival rates due to many causes. But there is no more lethal enemy of early film than fires.

Approximately 90% of American silent films are considered lost, as well as 50% of sound films made before 1950. In a study by the Library of Congress, it found that of the 11,000 silent films that were produced by the American movie industry between 1912 and 1929, only 14% (1,575) survive today in their original release condition, while another 11% survive in various imperfect formats. The combustible nitrate-based film of the silent era is largely responsible, leading to major fires at studio or storage vaults and film processing plants.

As early as 1920, the Lasky/Famous Players and Metro film exchange building in Kansas City caught fire. An unexplained explosion in a film vault in the shipping and examining room caused a fire that swept through the 12th floor of Lasky’s and then the 11th floor of Metro. $1,000,000 in films were destroyed but all employees were able to escape.

Closer to Hollywood and easier to recoup, a fire started at Universal City on May 23, 1922 when a short-circuited electric wire, “whipped like a flail” set film on fire in the cutting room of the studio. The heat caused boxes of film to explode with shards of metal flying in all directions. Actress Priscilla Dean, still in costume, tried to retrieve her film, “Under Two Flags ” but tripped on her robe and sprained her ankle. Irving Thalberg, then general manager, and Leo McCarey tried to reach the fire but were turned away. In this case the production just had to begin again.

One year later, a fire broke out at the Goldwyn Studio in Culver City (future M-G-M lot) on June 15, 1923. Some twenty films stored in the processing lab plus prints and negatives of seven partially completed films were destroyed in a fire at the lab. Actors Lew Cody, Edmund Lowe, directors, prop men and then fire crews put out the fire.

More seriously, the October 28, 1929 fire at Consolidated Film Industries, a film processing plant, killed a technician who nonetheless staggered out of an exploding and burning building with cans of film in his arms. Five others were burned and $2,000,000 in films were lost. Fifty other employees on the night shift escaped. A machine that polishes the developed film caused the initial fire. The plant was adjacent to Paramount and RKO studios, where some of their stages caught on fire. Films starring Douglas Fairbanks, Bebe Daniels, Mary Pickford and Norma Talmadge were lost.

Deadly fires were now becoming the norm. A catastrophe in film history occurred in Little Ferry, New Jersey. There 20th Century-Fox had a film storage facility, and on July 9, 1937, neglect and circumstances combined to ignite a fire. Nitrate film was long known to be unstable and prone to spontaneous combustion when exposed to heat. In the Fox storage vaults, made of concrete, poor ventilation and excessive summer heat caused gases from the nitrate film to spontaneously catch fire. A domino effect of fires destroyed them all. One youth was killed in the adjacent neighborhood, and two were injured. For film history, the loss was irreparable: most of the silent films from the Fox Film Corporation and many pre-1932 were lost. The Theda Bara films are lost except for some fragments, Some actors’ film work is unknown except by name. 75% of Fox films before 1930 were lost.

And then there was the MGM film vault fire in 1965. It occurred in the Film Storage Vault (#7 of the series) on Lot 3 adjacent to Jefferson Blvd. These vaults were built of concrete in the mid-1930s, separated from each other and far from any buildings. An electrical spark caused the fire and explosion that killed one person. The films of Metro Pictures, Goldwyn Pictures, and Louis B. Mayer Productions were lost, as well as several early M-G-M silents. These included Greta Garbo’s “The Divine Woman” and Lon Chaney’s “A Blind Bargain” and “London After Midnight.”

Studio fires destroyed more than film. A large fire destroyed parts of the Lasky/DeMille studio on April 30, 1918 located at Sunset and Vine. The cause was sparking electrical wires that ignited a rack of films in the color-room and tinting department, purchasing offices, stock room, glass stage set, and wooden buildings. Employees fought the fire while saving records, wardrobe, and films as best they could until L.A firefighters arrived. Costume designer and head of women’s wardrobe Alpharetta Hoffman along with C.S. Widom the Men’s wardrobe head managed to save the wardrobe from the 1916 “Joan the Woman” production. Valuable films in the vault were ordered to be removed to the street-side. DeMille was working on “Old Wives for New” when the fire started. The release was delayed a month and made from surviving negative copies. The colored positive copy was destroyed and the color process abandoned for the film.

Another fire at the old Fox studio on Sunset and Western started from crossed electrical wires at 2:00 a.m. May 20, 1928. A large sound stage was destroyed. The initiative and quick work of the Fox telephone operator Pauline Fuller had her at the switchboard calling studio executives and stars such as Charles Farrell, Victor McLaglen, Mary Duncan, Madge Bellamy and others to go to their dressing rooms and retrieve their wardrobes before the fire got to them. Nearly $200, 000 in damages was estimated.

Fires managed to hit many studios. Columbia’s 40 acre Movie Ranch in Burbank had a spectacular fire on May 26, 1950. The fire was probably started in the paint shop or lumber mill. It destroyed the power plant with two generators, the lumber mill, the water tank on its steel tower. Standing sets such as the New York street were mostly destroyed, as was the Western town.

One sound stage fire broke the heart of costume designer Irene Sharaff. On July 2, 1958 a fire broke out in the huge Sound Stage #8 at the Samuel Goldwyn Studio on Formosa Avenue in Hollywood, where the set for Columbia’s “Porgy and Bess” was located and being filmed. The raging fire in the early morning caused one entire wall of the sound stage to collapse into the interior of the building. The complete set for “Catfish Row” which Oliver Smith had designed and Prop man Irving Sindler furnished with a 30-year collection of props were all destroyed. Irene Sharaff’s complete wardrobe for the production was also destroyed. Stars Dorothy Dandridge, Sidney Poitier, Sammy Davis Jr. and Pearl Bailey were called and told not to come in for the dress rehearsal. Damage was estimated at $2,000,000 to $5,000,000.

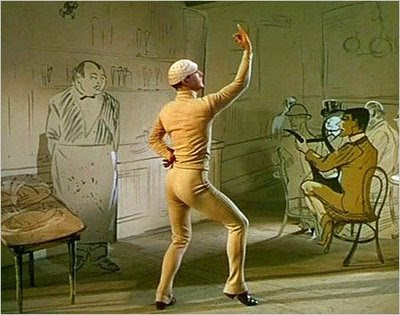

Another fire at MGM is sometimes confused with the 1965 film vault fire, but this one took place on Lot 2’s standing sets, where a fire started March 12, 1967 in a chapel and spread to Brownstone Street, where scenes from “The Easter Parade” had been filmed among other movies and TV shows. The fire continued to Waterfront Street and destroyed it. Despite its name, it fronted no water. It was used, with some redecoration, for “An American in Paris.” The fire was so hot it blistered the paint off a fire truck.

And another fire at the Samuel Goldwyn Studio at Formosa Ave. and Santa Monica Blvd. occurred on May 6, 1974. A large spotlight burned out and showered sparks on the TV set for “Sigmund and the Sea Monster.” Three sound-stages burned down before the fire was put out. Films such as “Dodsworth” and “The Best Years of Our Lives” had been made there. Although named the Samuel Goldwyn Studio, the lot was used for independent productions and TV shows in the 1970s. It had been a Hollywood studio since 1919, and once been the Pickfair Studio when Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks bought it in 1922. A few years later it became the United Artists Studio with their merger with Charlie Chaplin and D.W. Griffith. Goldwyn became a stockholder. Later still, Joseph Schenk and Darryl Zanuck rented the lot for use for their 20th Century Pictures before they merged with Fox.

Now much progress has been made in the safety of film and theaters, just in time for their disappearance. As for studio lots, well, they don’t make many movies there anymore either. Curiously, the Universal Studios lot had been used to store in a 22,320-square-foot warehouse, the master recordings and session masters of UMG, the world’s largest record company. These masters have been described as, “irreplaceable primary source of a piece of recorded music.” But on Sunday, June 1, 2008 after blow torches had been used on asphalt roof shingles on a standing set structure on the New England Street, it flared-up two hours after the work crew left and caused a fire. The New England Street burned as did the New York Street and the Courthouse Square used in “Back to the Future.” From there it burned down the wherehouse with the UMG music masters and recordings. And whatever videos and films also stored there Universal has yet to disclose.

Let’s be happy for the movies and music we still have, but recognize, like the family members, friends, and ancestors that are gone, what we have lost.

SOURCES:

- Los Angeles Times, Huge Lasky Film Fire. July 24, 1920 p13.

- Los Angeles Times, Blast Rocks Universal City. May 25, 1922 p I.

- Los Angeles Times, Millions in Films Endangered in Fire. June 16, 1923. II 3

- New York Times, Millions in Films Lost in Studio Fire. October 25, 1929 p28.

- Wikipedia. 1937 Fox Vault Fire.

- Wikipedia, 1965 MGM Vault Fire

- Los Angeles Times, Lasky Picture Plant Suffers in Spectacular Studio Fire. May 1, 1918 p I

- Los Angeles Times, Fox Studio to Build on Fire Ruins.May 22, 1928, p A1

- Los Angeles Times, Studio Fire Loss Set at $450,000. May 27, 1950 p A1

- Los Angeles Times, Goldwyn Studio Fire Razes $2,000,000 Set. July 3, 1958 p I

- Los Angeles Times, Fire Destroys Sets at MGM. March 13, 1967 p I

- Los Angeles Times, 3 Sound Stages Will Be Rebuilt, Executive Says. May 7, 1974 p3

- The New York Times Magazine, Judy Rosen, The Vault is on Fire. June 11, 2019

Views: 3524